Pity is underrated.

This is especially true when you have a friend going through a difficulty and you know all the answers to the questions they aren’t asking.

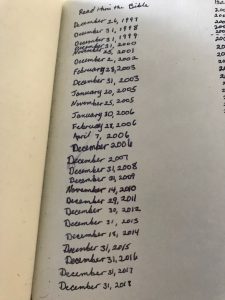

I just finished reading through the book of Job, which has become one of my favorite Old Testament books. (I’ve written a couple of previous posts about Job’s confusion and endurance.) While reading, I noticed again Job’s plea for pity from his friends.

You remember the story. Job lost everything—including his wealth and livelihood, his children, and his health. His friends came to comfort him, but rather than speaking words of consolation, they spoke words of condemnation, suggesting from a variety of angles that surely he was at fault for all that had befallen him and that if he would just confess the hidden sin they assumed he harbored, all would again be well.

But Job didn’t see it that way. He knew that while he wasn’t perfect, he had no hidden sin. As the conversations between the four men continued, Job often turned his words from addressing their accusations to simply crying out in anguish for relief and understanding from God. And multiple times, he asked for relief from his friends’ condemning words.

On one of these occasions, Job pled with his friends for pity: “To him that is afflicted pity should be shewed from his friend” (6:14).

Pity. Job just wanted his friends’ pity.

Job isn’t the only one in the Bible who longed for pity. Psalm 69:20 tells us that David wanted it as well: “Reproach hath broken my heart; and I am full of heaviness: and I looked for some to take pity, but there was none; and for comforters, but I found none.”

What is remarkable about Psalm 69 is that it is a messianic psalm specifically pointing to Christ on the cross. Of this passage, Matthew Henry wrote, “David penned this psalm when he was in affliction, and…the predictions were fulfilled in Jesus Christ.”

Read the verse again, and let this reality sink in: Jesus wanted pity. In His darkest hour, He longed for human pity and comfort.

Reproach hath broken my heart; and I am full of heaviness: and I looked for some to take pity, but there was none; and for comforters, but I found none.—Psalm 69:20

Sometimes we contrast pity and compassion, dismissing pity as a mere empty feeling. But what if true compassion requires pity?

What if there are times when, like Job’s friends, we don’t see the situation as clearly as we think we do? And what if we don’t have as applicable answers as we believe? What if, in some instances, pity is the best vehicle for giving comfort?

There are two perspectives from which this truth is needful to grasp—when you are the person who needs to give pity and when you are the person who needs pity.

When you can’t “fix it,” you can still give pity.

I think those of us who know that God’s Word holds all the answers for life sometimes forget that we aren’t personally responsible or able to fix everyone’s pain. Sometimes, as in Job’s case, God allows suffering to continue for reasons known only to Him. Sometimes, like Job’s friends, we are too quick to assume what we don’t know and too impatient to listen when visible change doesn’t immediately take place.

But when we can’t “fix it” for our friends, we can still care. We can empathize. We can be okay with not being the hero and just be the encourager, affirming God’s compassion and care as we walk alongside one who is suffering.

Much of the book of Job is a record of the dialogue between him and his three friends. For chapter after chapter, the pattern is predictable. He speaks; they accuse.

But have you ever considered how Job’s suffering would have been made more bearable had his friends encouraged him? What if they had said, “We don’t understand either, but we trust God with you”?

When you need pity, God gives it.

I first noticed the messianic prophecy, “I looked for some to take pity,” during my Bible reading one morning years ago. It came on the heels of a difficult realization that a friend who had tried to fix something in my life which she didn’t understand had given up on caring as well. As I read these words describing Jesus’ experience, I understood in a more profound way than ever before, that He cares.

Jesus understands the need for sympathy. To once again quote Matthew Henry on Psalm 69, “We cannot expect too little from men (miserable comforters are they all); nor can we expect too much from God, for he is the Father of mercy and the God of all comfort and consolation.” (Incidentally, Henry’s parenthetical thought there is a reference to our friend Job: “I have heard many such things: miserable comforters are ye all,” 16:2.)

Even in Job’s case, as poor, miserable Job believed he was cut off from God and was pleading with his friends to just show pity, God Himself was looking on Job with great pity and tender mercy: “Ye have heard of the patience of Job, and have seen the end of the Lord; that the Lord is very pitiful, and of tender mercy” (James 5:11).

Pity is a gift.

Whether you are a frustrated friend who can’t seem to get her message of help across to one who is suffering or you are the anguished sufferer, remember that pity is a gift. There are times we need to give it, and there are times we need to receive it.

There are unexplainable griefs in this life. Sometimes God allows His own to shoulder burdens that don’t go away in a single conversation…or decade. Sometimes we do well to listen and care and walk with our friends to the throne of grace again and again—not in a short-lived quest for the perfect solution, but in assurance (and giving reassurance) of “mercy, and…grace to help in time of need” (Hebrews 4:16).

And then, when we pour out our heart and pain before someone from we hope to receive the gift of pity, and they don’t know how to—or just don’t—give it, we do well to remember that God empathizes with us.

The God who pitied Job is the same who Himself felt the loneliness of suffering without comfort. He is “touched with the feeling of our infirmities” (Hebrews 4:15), and He invites you to cast all your cares on Him, “for he careth for you” (1 Peter 5:7).